Missing Children

The first in a series of

The shortage of licensed foster care homes is critical, and children — especially siblings — often have nowhere to go in a crisis. Kids Central Inc. is working to ensure foster children get the care and love they need.

PHOTOS: Matthew Gaulin+Cal Gaines

Imagine strangers coming to your door and saying you have to leave with them immediately.

You can’t take your dog or your favorite toys. The person you love the most — your mother — can’t go with you either. If you are very lucky, you might get to stay with a relative; if you are a little lucky, you might be placed with a caring family.

But many youngsters aren’t so fortunate. They find themselves among other scared children in a group home or in a succession of temporary foster homes.

“These are war-torn children,” says Rosey Moreno-Jones, who’s in charge of foster parent recruitment for Kids Central Inc., a nonprofit organization that manages a comprehensive system of care for abused, neglected and abandoned children and their families. “These children are often traumatized and do not know what’s coming next.”

In the late 1990s, Florida transitioned from a government-based child welfare system to community-based agencies in each of Florida’s 20 judicial circuits. Kids Central, which serves the Fifth Judicial Circuit of Lake, Sumter, Citrus, Hernando and Marion counties, works with the Florida Department of Children and Families to provide services for abuse-prevention, diversion (when a child is able to remain at home with supervised care) and foster placement.

“We do a lot of prevention and a lot of diversion so children can stay in their homes,” says Nicole Pulcini Mason, director of community affairs for Kids Central. “If protective investigators determine the child needs to be removed from the home, they call us. Foster parents are the backbone of what we do when we get those calls.”

The Foundation for Government Accountability, a free-market think tank, ranked Florida fourth highest in the nation in 2012 for its success in reducing abuse and responding quickly to abuse allegations through community-based agencies such as Kids Central.

“Kids Central is the front door and the back door for these children,” adds Moreno-Jones. “We manage their care from the time they enter the system until they leave, whether it’s returning to their homes, getting adopted or aging out of system.”

Keeping families, especially siblings, together is a priority. Case managers work with biological parents to assess situations and get the services they need to deal with problems, including domestic violence, drug abuse, mental illness, and neglect and abandonment. In the meantime, children often must be removed from the home.

“We want the children to stay with a family member whenever possible,” says Mason. “Foster care is one of the last resorts, and a group home is the very last resort. Unfortunately, group homes are still a necessity.”

In Florida, almost 8,600 children are in licensed care foster-care homes with a total of 4,727 licensed homes statewide, according to DCF. In the five-county region served by Kids Central, almost 2,000 children are in the child welfare system. Approximately 350 of those children are in actual foster care in 185 licensed foster homes.

“It may sound like we have enough beds for these children, but not all of them work for what we need,” says Moreno-Jones. She cites an example of a willing foster parent who had a cat, but the child was allergic.

On a recent Monday morning, Kids Central case managers were busily calling foster parents to see if any had extra beds for 15 children, including several sibling groups who came into the system over the weekend.

“One of our biggest challenges is finding foster-care homes that can take brothers and sisters,” says Moreno-Jones. “We refuse to split siblings. A sister or brother is the person you know the longest for your whole life.”

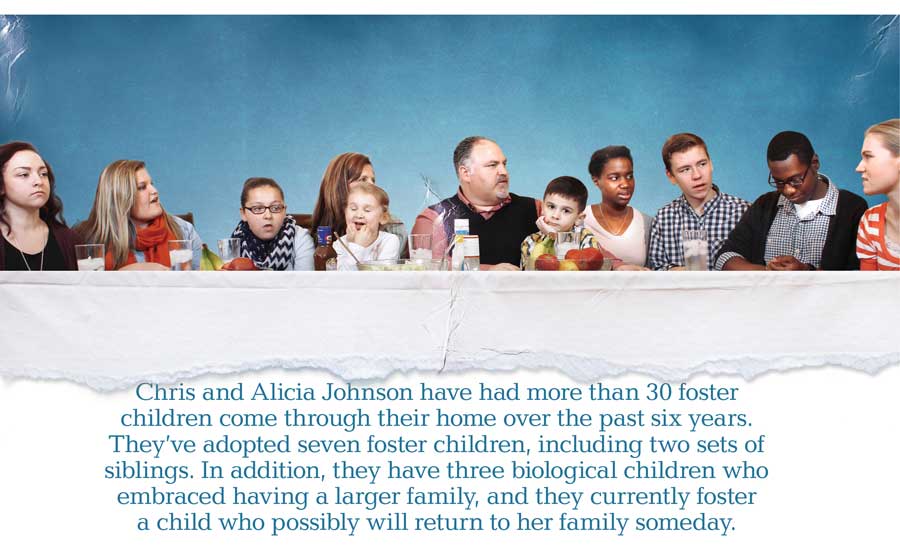

“We’re passionate about it,” says Chris, who is the senior pastor for Clermont’s Liberty Baptist Church. “These children are already separated from their parents, and staying with their siblings helps them to better deal with the situation.”

The Johnsons have had more than 30 foster children come through their home over the past six years. They’ve adopted seven foster children, including two sets of siblings. In addition, they have three biological children who embraced having a larger family, and they currently foster a child who possibly will return to her family someday.

Teenagers and aging out of the system

Another challenge at Kids Central is placing teenagers, who often bounce from foster home to foster home.

“Being in foster care does make you grow up fast,” says Louis New, a former foster child who now works at Kids Central as an independent living coordinator to help teenagers aging out of the system. “There was no stability in my life.”

From 1991 until 1999, Louis lived in 13 different foster homes, first in New York and then in Florida. When he turned 18, he joined the U.S. Navy and “finally found a stable environment.” Now 33, he has two children of his own and a career where he feels like he’s making a difference.

“I know what it is like to be in their shoes,” says New. “I can relate to struggles foster teens are having. I push them to go to school, but I also hold them accountable.”

Nine of his independent living students (children 18 to 22 who are transitioning out of foster care) are in college and another is in her senior year of high school. Teenagers are no longer automatically turned out of the system when they reach 18. Foster care can extend until 22 if the young person is in school, or age 23 if he or she has a medical disability. Those attending a Bright Futures college can get $1,256 a month for college through Florida’s Post Secondary Education Service Support program.

“Independent Living is a benefit other states don’t have,” Louis says. “It works when it’s used right and not as a crutch. It is central to helping these kids become successful.”

Foster parent recruitment

The biggest challenge remains having enough foster parents to take in children and teens who are often caught in inconceivable situations. While many people want to open their homes to help, it’s not as easy as just offering a bed. Florida has strict guidelines for becoming a foster parent and licensing of foster homes. It also takes four to six months to become a foster parent.

“Kids Central holds parents to an even higher standard,” says Moreno-Jones. “They cannot be on unemployment or receive public assistance. They must have the resources to do this.”

Potential foster parents undergo background checks and financial screenings and must attend an orientation followed by 10 weeks of intense training before a child is placed in their care. Home study also continues. They receive a stipend of $17 a day per child to take care of necessities. Florida limits the number of children in foster-care homes to five, with exceptions when siblings are involved.

“There are many myths about being a foster parent,” says Moreno-Jones. “They don’t have to be young, wealthy or a married couple with a stay-at-home caregiver. Love, stability and responsibility are what matters most.”

She adds: “Our foster parents are part of a team — a village, so to speak — committed to nurturing a child’s well-being and to strengthening and mentoring the child’s family if and when the child returns to them.”

CLOSE TO HOME: Sabrina’s Story

Sabrina and her husband, Joe, are juggling careers while caring for three foster children in addition to their three other children.

Sabrina, who was an only child, always wanted a large family.

“At least seven,” she says with a laugh.

She has two biological children, Sierra, 23, and Tristan, 17, and an adopted daughter, Mia, 10. She thought her family was complete until she slowed down and listened to her heart and to God.

“God revealed to me I was now in a position to have a big family,” she says. “I quieted myself enough to hear what He wanted.”

Almost two years ago, she and Joe attended orientation and training classes at Kids Central. They’ve since fostered eight children, including two newborns at one time, and are in the final stages of permanently adopting one of their foster children, Anthony, who will be 2 in June.

The couple’s older children totally embraced the idea of opening their home to foster children. Fifth-grader Mia, who came to the Ciceri home when she was 10 months old, summed it up best: “It didn’t take long (for us) to realize how important fostering was. Our house often has chaos, but we don’t mind because we’re helping other children.”

Kids Central Inc. recognized the couple’s commitment and named Sabrina and Joe 2014 Foster Parents of the Year.

“Sabrina and her husband are stellar examples of what we want foster parents to be,” says Mason. “They believe this is a calling and live it to create a loving environment for these children.”