Smart Clark

America’s consumer warrior doesn’t love money. Really, he doesn’t. He’s just crazy about saving it.

The gangly gent adjusts eyeglasses bought on the Internet for the price of a large pizza as he talks on a Chinese phone while sitting at a conference table he found on Craigslist.

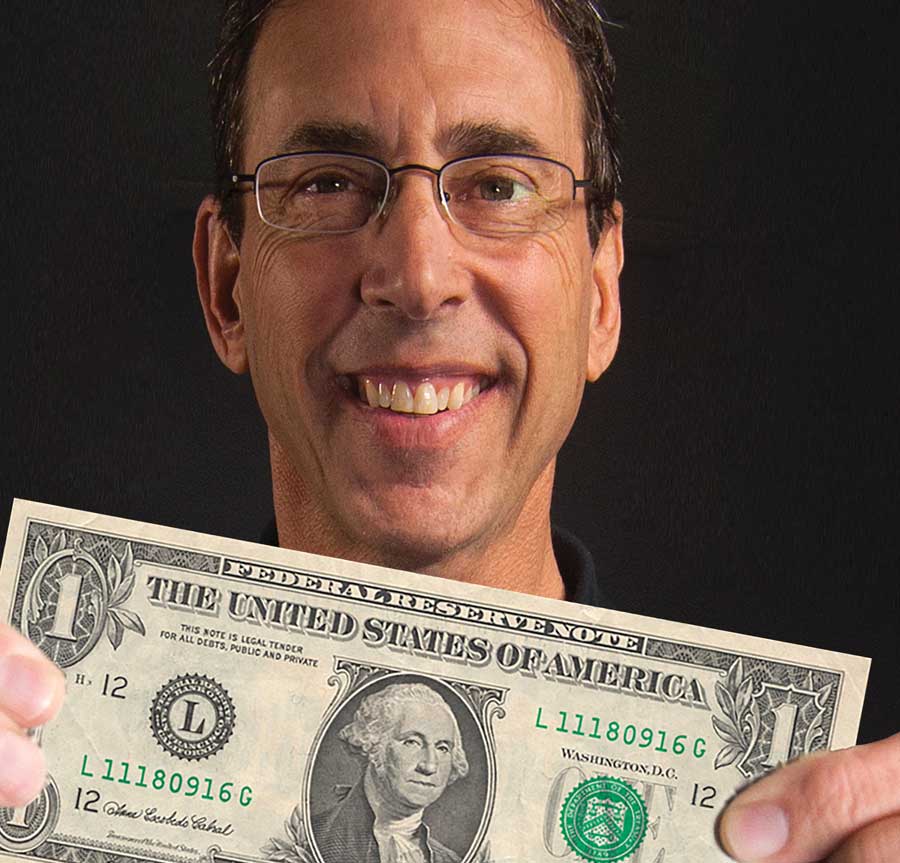

When posing for a photo, he doesn’t say “cheese,” he sings “cheeeeaap.”

Go ahead, laugh. Clark Howard is guffawing all the way to the bank.

America’s consumer warrior is worth $15 million from spreading the gospel of “save more, spend less and avoid rip-offs” in 10 books he’s authored, on 200 radio stations, Turner Broadcasting’s HLN and the Internet.

Clark obviously knows how to make money. But – surprise – he’s not nutso about greenbacks. Clark Howard would rather save a buck than make one.

That’s why he wears glasses purchased at ZenniOptical.com for $37, talks on ZTE Zmax cell phone (no annual contract!) and bought a $2,000 conference table off Craigslist for $175.

There’s a big difference between loving money and hating to waste it.

“People automatically assume before they really know me that I’m one dimensional, and that everything is about money. And that’s not the case at all,” Clark says from the living room of the $4 million Atlanta home he shares with wife Lane and their three children.

“You can’t be. You’d be pretty lonely and lead a pretty dull life if everything was about money. Study after study has found that money can make you unhappy if you don’t have any, but once you reach the point that you can cover the basics, money as an identifier of happiness trails off really quickly.”

Clark’s basics have been covered since he arrived on June 20, 1955.

“I grew up, what I call a child of privilege,” he says matter-of-factly. “We had lived a very, very nice life. My parents were in a country club. They were living a very high life.”

And then … now pay attention, because this is when the pied piper of penny-pinchers was born.

“My father worked 30 years for his father-in-law’s business. When his father-in-law died, the business hit a rough patch and he got laid off,” Clark recalls. “I had no clue there wasn’t a lot of money around. I didn’t know they hadn’t saved any money until I came home from college.

“It was very solemn in the house. I thought my dad was going to tell me he was dying. Because it was that gloomy in the house. After dinner, he asked me to stay at the table. And I was like, ‘Okay, this is it, he’s going to tell me what he’s dying from.’ And instead, he told me he had been fired from his job. And I started smiling and he’s like, ‘What are you smiling about?’ And I said, ‘Well, I thought you were dying.’ And then he laughed.”

The smiles and laughter didn’t last long.

“And then he said, ‘I don’t know how much longer I can pay for your college.’ And I was like, ‘What?’ Because I just thought my parents just had an endless trough of money, which I think a lot of kids think their parents do. So that was a key defining moment in my life.”

Clark responded by moving out of the dorm on the American University campus (in Washington, D.C.) and registering as a night student. Next, he moved into a rundown apartment building (“My apartment rent was $257 a month – Not that I remember.”), got a full-time job as a bill collector for IBM and rode the city bus to and from work.

“My days started very early and I finished school at 10 o’clock,” Clark says.

He was not a typical college student.

“Animal House came out either while I was in college or right afterward, and I saw the movie and I didn’t understand why it was funny. Because I didn’t have any of those experiences at all.”

While other kids partied, Clark developed a self-discipline and work ethic that would lead him to fortune, and later, his calling as a consumer advocate.

“That was the best thing that happened to me,” he says. “I became obsessed with not spending money.”

Clark’s frugality allowed him to bank every other paycheck. After graduation he moved back to Atlanta and opened a travel agency.

“I started that when I was 25 years old. And it was the right business at the right time because the airlines had just been deregulated. Before that the government decided what the prices would be, who would fly the route, what time of day they could fly, how many times a day they could fly. It was like a straightjacket so only the wealthy privileged flew,” he says. “Before deregulation the percent of people who flew was teensy tiny. And now it’s huge.”

Within five years, Clark was one of the wealthy privileged.

“I retired the first time when I was 31,” Clark recalled. “I had expanded my travel agency into five offices. I opened a new office about every 18 months.”

And then he sold.

Clark the retiree unwound at the beach, rode his bike 20 miles every day, swam another two miles and watched reruns on TV.

“I had worked so hard in that business for six years, that when I sold it I was like, relieved … so I was here doing really nothing, except my athletics.”

And then, another “key defining moment.”

“I got a call on a Friday afternoon in the fall of 1987 from a producer at WGST Radio. They used to have a weekend lineup of how-to shows, self-help shows, and they had a travel show and their guest expert had cancelled for Sunday. And the producer asked if I could come in. Well, my schedule was so busy I said, “Sure.” Everything that happened to me in broadcast, happened because of that one guest appearance.”

Today, radio is just a small part of the Clark Howard empire.

“In 1987, there was no Internet. Personal computers were basically glorified word processors and accounting machines,” he says. “I’ve never stopped morphing in how I reach people. The information is the sun, radio is one planet and TV another, but the big planet today is digital. People accessing me on their phones is the fastest growing way people access me.”

He’s doing pretty well on social media too. Clark’s Facebook page has 434,000 likes. By comparison, CNBC financial advisor Suze Orman has 416,00 likes and NBC Mad Money host Jim Cramer has 58,855.

Which begs the question, “What does Clark have that other high-profile money managers lack?” For starters, humility.

“For me, the information is the star,” he says. “It’s not about me, it’s about the information.”

You have to love a guy who lets — make that encourages — people to criticize him on his own show. In fact, Clark is thrilled that “Clark Stinks” has become the most popular feature on his radio broadcast.

“I’ll tell you how ‘Clark Stinks’ came about. Years ago there were all these websites that people registered, like ClarkHowardsucks, and several competing ones that were just piling on,” he recalls. “And I thought, ‘If people really feel that way about me, we should let them say it in our own house.’ It started off as a one-time thing. We got feedback, and people loved it … I say we’re all in it together and that I shouldn’t have the last say. And I mean it. I’m a flawed human being, I might be wrong. So I’m giving people a chance to let off steam.”

Still think Clark Howard is just about money?

By now, it should be clear that Clark’s stayed on top for 28 years because he’s about Bens and Bonitas, not Benjamins.

“I just believe that the greatest joy in life is doing things for others. That’s what brings me the greatest satisfaction,” he says.

But one person can only do so much, so Clark opened Team Clark Howard’s Consumer Action Center, which he staffs with volunteers who provide advice and problem resolution — free of charge — to callers.

“We care about people and we all want people to have better lives,” says Clark, who opened the center 22 years ago.

Clark also gives back to the community by sponsoring (40 so far) and helping build Habitat for Humanity houses in and around Atlanta.

In this, his 20th year as a Habitat volunteer, he’ll help build “57 to 62.” And he’s in his 14th year as a volunteer in the Georgia State Guard.

“The charities and the community activities I’m involved in are central and core to who I am,” Clark says. “We as Americans think we identify by what we do for work, but the reality is, at the end of the day, what really matters is who we are as people.”

Clark Howard has been comfortable with himself since he began working for people instead of a paycheck. And the more he gives of himself, the happier he gets.

“Things don’t make you happy. I believe experiences make you happy,” Clark says. “The things that really matter to me, are obviously my family, and then doing what I can to make the community better.”

[row] [column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]

Clark’s barks

3 simple ways to be Clark Smart

1: Attack the monthlies. And any kind of subscriptions. People have subscriptions to stuff they don’t even remember. They might have signed up for Netflix, which is a great thing, but they might never watch it. I like people to look through credit card statements and bank statements to find monthlies that they never use.

2: Get a little spiral notebook – not an app on the phone … and any time you spend money, write it down. What happens is amazing. Because you have to physically take the pencil out and write everything down, it starts a whole new wave of thinking: ‘Do I really need that? Should I be buying that?’ It really does make you stop and think. It only takes two weeks of doing that for people to see there’s a lot of money they’re throwing away that they don’t need to spend.

3: A lot of people feel that the debit card is the answer because if you use a debit card, you’re only spending money you already have. But if someone has a problem using plastic, I like them to go to a cash allowance. Decide how much cash comes out of every pay period and live on that amount of cash for everything you do walking around for 15 days, a month, two months. What happens is you see the cash dwindle. You don’t have that perception with a piece of plastic. Maybe you normally don’t think about spending $6 or $7 for lunch, but if your cash is really getting light and you’re several days from the next draw of cash, maybe you make your lunch that day and take it with you. It’s all about changing behaviors.[/column]

[column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]